On Feature Films and RoI (return-on-investment)

At the risk of repeating some things over (again), and even, tautologically:

In the most comprehensive statistical economic survey of the feature film domain to date, Entertainment Industry Economics, Vogel states

‘…of any ten major theatrical films produced, on the average, six or seven may be broadly characterized as unprofitable and one might break even.’

This problem has been consistent for over 20 years, as the records show that, likewise, in 1990: on average, 2 in 10 films made money, 1 in 10 films `broke even’ and 7 in 10 films lost money (Vogel 1990: 70).

The Australian and UK film industry figures are similar. (FilmVictoria 2011)

Likewise – De Vany also finds that:

`Seventy-eight percent of movies lose money and only 22% are profitable.’

Note – this is the same result as `7 in 10’…

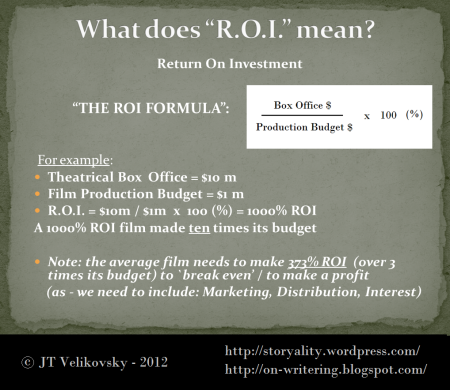

What actually is `RETURN ON INVESTMENT’?

The formula for calculating RoI is: to divide the film’s box office (in dollars) by the production budget in dollars (“negative cost”), and multiplying the result by 100, and expressing that number as a percentage.

So – a film that made a 300% RoI made 3 times its production budget. A film that made a 1000% RoI, made ten times its budget. (Successful `blockbusters’ like Avatar make about ten times their budget, or 1000% RoI. But the top 20 RoI films, the subject of my empirical doctoral research study, all made over 70 times their budgets. Seventy times. That’s a lot.)

How much does a film need to make to `break even’?

You might assume that a film needs to make the same amount as its budget, to `break even’. That is, a film that cost $1m to make, needs to make $1m at the box office to break even. However by my calculations, the average film needs to make 373% ROI, to break even.

…Why is this so?

Feature films usually have the same amount spent on marketing (advertising) as the budget of the film. If a film cost $1m to make, then a “rule of thumb” is to also spend $1m on marketing. Likewise, if a film cost $50m to make, generally, $50m is spent on marketing. Suddenly – the film needs to make a 200% ROI, just to break even.

In fact, regardless of the film’s budget, most films need to spend a minimum of $1m on marketing, just to ensure that the cinema-going audience knows that the film exists.

As Arthur De Vany states in his excellent study, and collection of research papers, Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes the Film Industry (2004):

“The frightening thing about trying to manage this [film] business is that there are no tangible means to reliably change the odds that a movie will succeed or fail. Marketing can’t change the odds. There is no evidence to show that marketing has much to do with a film’s success. Marketing is mostly defensive anyway; a studio has to market its films draw attention in a field where everyone is shouting. If you don’t shout too, you will be drowned out and may not be noticed.”

In Entertainment Industry Economics, (Vogel 2011) Vogel also shows that films in general spend the same on marketing as the film’s budget. (Vogel 2011: 143)

This may seem obvious, but: Films also take time. Vogel points out that:

“Beginning with a rudimentary outline or treatment of a story idea, it can often take over a year to arrange financing, final scripts, cast, and crew. In total, it normally requires at least 18 months to bring a movie project from conception to the answer-print stage – the point at which all editing, mixing, and dubbing work has been completed.”

In fact, it can take 15 years. (See the screenplay for the film, Forrest Gump…) Bloore (2013) in The Screenplay Business notes it can take from 2 years to 8 years.

So, what is the opportunity cost? If you invest $1m in the bank, and on that term deposit you can get a 5% RoI over 2 years, then, you have lost that with investing in a film (where, certainly, the `risk versus reward’ ratio is vastly higher. 7 in 10 movies lose money; very few banks go bust. Well – except in a Global Financial Crisis, of course).

So then, what exactly is `The RoI formula’?

Note that – the studio (or, the distributor, if it wasn’t `a studio production’) gets 55% of the box office.

And so – RoI = (0.55 x Box Office$ – Production Budget$) / Production Budget$

If that division-sum comes out at `1′, then, you `broke even’.

So — if you punch some numbers in to that formula, to get a 1.05 return:

(i.e. – note that, “break even” is really 1.05, given that, you can get 5% interest on a fixed term deposit in a bank, for the 2 years or more that a film takes to make. i.e. the `opportunity cost’.)

The result is: 373%.

So if you make a film for $2m, (i.e. – a $1m `film negative cost’, + $1m marketing & distribution) you need to make $7,450,000 (373% ROI) just to break even.

The source for this formula:

RoI = (0.55 x Box Office$ – Production Budget$) / Production Budget$

is from:

Eliashberg, J, Hui, SK & Zhang, ZJ 2007, ‘From Story Line to Box Office: A New Approach for Green-Lighting Movie Scripts’, Management Science, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 881-93.

I note, that particular study (on whether film story affects RoI) was done by the Wharton School of Marketing, at the University of Pennsylvania – but that study is, in my view, deeply problematic.

However `the RoI formula’ seems absolutely correct. (i.e. RoI = (0.55 x Box Office$ – Production Budget$) / Production Budget$) )

So – at the `indie filmmaking’ end of the spectrum: it means – if you make a feature film for $1000, and spend $1000 on Marketing, you need to sell 746 tickets at $10 each, to go see the movie. (i.e. $7460) and, you are at `break even’.

Note that some films on the top 20 RoI list were made for $7,000.

Stanley Kubrick on RoI…

Notably, Kubrick is one of the true geniuses of cinema. (See how many of his films are considered canon, or classics of the genre, for example at The AFI’s 100 Years 100 Movies, or the Sight & Sound Critics Polls, or Empire Magazine’s Best 301 Movies, or IMDB.com’s Top 250 or maybe just ask any professional filmmaker or critic at random, and – chances are pretty good – they’ll tell you the `one true genius of cinema’ was Kubrick… ) He in fact was a genius in lots of domains (and film is obviously composed of many domains, including the sciences and the arts) but anyway, all this also correlates with something he stated. – This is not to suggest he’s done an empirical study, but actually – knowing Kubrick, he probably did…

Here is what Kubrick said, in an interview with Michel Ciment, in Kubrick (Ciment 1983): (yes he was writing this in 1981, but if you check the figures, it still applies!)

`Ciment: Today it is more and more difficult for a film to get its money back. The film rental can be three times the cost of the film.

Kubrick: Much more than that. Take a film that costs (USD)$10 million. Today it’s not unusual to spend $8 million on USA advertising, and $4 million on international advertising. On a big film, add $2 million for release prints. Say there is a 20% studio overhead on the budget: that’s $2 million more. Interest on the $10 million production cost, currently at 20% a year, would add an additional $2 million a year, say, for 2 years – that’s another $4 million.

So a $10 million film already costs $30 million. Now you have to get it back. Let’s say an actor takes 10% of the gross, and the distributor takes a worldwide average of a 35% distribution fee. To roughly calculate the break-even figure you have to divide the $30 million by 55% , the percentage left after the actor’s 10%, and the 35% distribution fee.

That comes to $54 million of distributor’s film rental. So a $10 million film may not break even, as far as the producer’s share of the profits are concerned, until 5.4 times its negative cost.

Obviously the actual break-even figure for the distributor is lower since he is taking a 35% distribution fee and has charged overheads.’

(Kubrick in Ciment 1983, p. 197)

So, one question is, this: If the film story is the reason a film succeeds (and of course, can also be one reason it fails – if the story is not a viral story) – the screenwriter – in the USA – gets 5% of the movie budget (and some back-end profit points if they are incredibly lucky.)

In Australia, it is actually: just 3% for the writer. Think about that! (Note: …Is that fair? Do the key creatives – eg those who create the story/screenplay, that becomes a film) get their dues? (Or, should something change?)

The Economics of Movies…(!)

`Complicating the picture all the more, the relationship between budget and profits is not necessarily linear. More is not always better. For example one study found that profits were a backward-J function of budget.

That means it’s the low-budget pictures that are most likely to make the most money. Costing the least to make, they don’t have to bring in as much at the box office to earn a sizable return with respect to the investment.

The extremely low-budget The Blair Witch Project brought in $141 million in domestic gross. A more recent example is the 2003 Open Water that grossed about $31 million but cost only about $130,000 to make.

By comparison, even when a big-budget film does make money, it’s more likely to earn less relative to the cost. According to one analysis, more than a third of the big-budgeters will generate losses. But at least that’s better than the poor expected return of middle-budget films.’

So, one strategy is: to look at the top 20 RoI films – and work out what made them successful.

(Answer: The Story.)

…Thoughts? Comments? Feedback?

——————————————–

High-RoI Story/Screenplay/Movie and Transmedia Researcher

The above is (mostly) an adapted excerpt, from my doctoral thesis: “Communication, Creativity and Consilience in Cinema”. It is presented here for the benefit of fellow screenwriting, filmmaking and creativity researchers. For more, see https://aftrs.academia.edu/JTVelikovsky

JT Velikovsky is also a produced feature film screenwriter and million-selling transmedia writer-director-producer. He has been a professional story analyst for major film studios, film funding organizations, and for the national writer’s guild. For more see: http://on-writering.blogspot.com/

————————————

REFERENCES

De Vany, Arthur S. (2004), Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes The Film Industry (Contemporary political economy series; London ; New York: Routledge) xvii, 308 p.

De Vany, Arthur S. and Walls, W. David (2004), ‘Motion picture profit, the stable Paretian hypothesis, and the curse of the superstar’, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 28 (6), 1035-57.

Eliashberg, J, Hui, SK & Zhang, ZJ 2007, ‘From Story Line to Box Office: A New Approach for Green-Lighting Movie Scripts’, Management Science, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 881-93.

FilmVictoria (2011), ‘Australian Films at the Australian Box Office’. <www.film.vic.gov.au/__data/…/AA4_Aust_Box_office_report.pdf>.

Simonton, Dean Keith (2011), Great Flicks: Scientific Studies of Cinematic Creativity and Aesthetics (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Vogel, Harold L. (1990), Entertainment Industry Economics: A Guide for Financial Analysis (2nd edn.; Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press) xvi, 432 p.

— (2011), Entertainment Industry Economics: A Guide For Financial Analysis (8th edn.; New York: Cambridge University Press) xxii, 655 p.

Pingback: StoryAlity #45B – On Tracking Memes in The Meme Pool | StoryAlity

Pingback: StoryAlity #61 – On The Storyality Probability Calculus – and the Principle of Induction | StoryAlity

Since your ROI talks about indie films, I think it needs to reduce the box office return by an additional 50%, taking into account the distributor’s cut prior to paying the indie producer. So the formula for indie films would be:

ROI = ((0.55 x Box Office$) x 0.50) – Production Budget$) / Production Budget$))

or:

ROI = (0.275 x Box Office$) – Production Budget$) / Production Budget$))

So, for the $2,000 indie film, 1,490 tickets would need to be sold.

Hi Tim

Thanks so much for the Comment.

Hmm – But isn’t the 50% included in this formula/figure?

ie: See, from above: “Note that – the studio (or, the distributor, if it wasn’t `a studio production’) gets 55% of the box office.”

So, if it *was* a studio (like say: `Star Wars’ 77, or `ET’), then – they (the Studio) do the Distribution, right? And: take their 55% for this.

And – if it *wasn’t* a Studio, and was an independent Distributor, then – they (the Indie Distrib) are the ones taking that 50% out (as opposed to: 55%).

ie It is `indie Distribs’ taking their cut, instead of: one of the 7 major Studios (which, have their own Distribution arms) taking it.

So – the reason it comes out the same (around 55%), is: since this is an Average, if you add the 17 x 50% (for the 17 indie movies in the Top 20 ROI Films) and the 3 x 55% (Star Wars and ET, and by the time you include My Big Fat Greek Wedding), it comes out close enough to 55% to make, 55% the average.

So, 373% ROI to hit `break even’ is really just an Average. (ie – Results May Slightly Vary, in each specific case…)

ie Tim – I am not saying you are wrong if you look at a specific case, but for the $2000 indie film, I think you still need to sell 746 tickets?)

Forgive me if I am missing something, I often do. 🙂

ie Either the Indie-Distrib – or the Studio/Distrib takes the 50% – or the 55%. But – they wouldn’t take both?

As – you would only need/have: one, or the other?

Anyway as I say – it’s an average. In each specific case, you would need to check, who takes exactly what…

Also, that specific ROI break-even question, also takes into account, the question of: the Producer’s pay. (And before they even pay out anyone with Profit Points. eg Actors, Crew, etc.)

(And – don’t get me wrong, to have a *sustainable* film career – especially as a Producer – that is a super-important economic question,

ie – you are totally right, to raise it!)

But, as you would know, the `overall StoryAlity research’ really just aims to look at: Audience Reach (using the metric of: tickets sold) / Production Budget (ie – not including Marketing or Distrib costs).

i.e. The Question being: Why exactly do some films (and: not others) go so viral, due to: word-of-mouth…

And How cheaply can you get your Film Story in the can (no matter whether the story is Primer – or Star Wars, or ET) and still get a cinema release (and ideally then: it goes viral)

ie The purpose of the research is not actually focussed on The Money – and How Much You Can Make (as counter-intuitive as that sounds, given the term: RoI.)

ie Of course, a side-effect of having a superviral film story is: there is then a lot of money floating around.

But the empirical research here shows – it was the virality of the Story, nothing else – that actually caused that to happen.

And – who actually *gets* that money? ie Sees, the actual profits?

Ironically, most of the Writer-hyphenates in the Top 20 ROI Films (the creators of the Story) rarely saw a lot of cash from their superviral film story.

ie I believe, John Carpenter was paid $50k in total for Co-Writing and Directing HALLOWEEN, with its $325k budget – and its $70m of cinema box-office takings.

ie $50k…! That’s not a lot of dough, for 2 years’ hard work…!

Same for Stallone in Rocky – after writing it, he took a tiny fee ($18k) for the script, so he could star in it… etc.

Anyway so – the point is not just `to make money’ (not that there is anything wrong with that, money is great), the point really is: How to write a film that will go superviral. Once you do that your 2nd (or: subsequent) film will be vastly easier to finance.

Cos – the writing is actually the easy part, right?

But – 98% of scripts presented to producers go unfinanced, and therefore: go unmade.

See: StoryAlity #18 – THE PROBLEM: 7 in 10 FILMS LOSE MONEY (and 98% of Screenplays Go Unmade)

So – How do you get into: the 2% that get made?

This research aims to provide empirical and scientific answers to that question.

(And of course – when they read a script, Producers can also use the StoryAlity Checklist – as a benchmark/probability calculus, to judge the probability of the film story in question, going viral…)

As – The biggest issue I have found professionally, having had about 15 feature scripts optioned, and having written about another 15 on commission but only having a few produced, is: the Financing.

ie Producers may LOVE the script and option it – but then the financiers (guys with all the money) all seem to have *no freaking idea*: What Will Work.

ie They can’t recognize a viral film story, when they read it.

(Partly this is due to “words on paper” being such an abstraction. ie FIlms are: sound and image. Everyone’s imagination is different and most guys with lots of money seem to have: very little of it – LOL)

Everyone (mistakenly) assumes that they understand `Story’, without ever taking 10 years to properly study Film Story.

Or – without even looking at the Top 20 ROI Film’s Stories – and, what they all share in Common, and also: What the Bottom 20 ROI Films do wrong, in their Story.

Which – is why – the big studios all just have a crapshoot and they fund a slate of 10 random films at once. As – the `3 in 10′ will – hopefully – make back all the money they gambled and they won’t go out of business. (Though – many of them still even manage to screw that up.)

So I’m simply trying to show them: What has empirically worked, before… in viral film Story.

(And indeed, not just the Studios, but – the Indie guys too…)

Anyway… Tim, thanks so much for reading, and commenting/engaging with this research – I really do appreciate it.

And let me know if I’m missing something (re: that ROI question you’ve raised. It’s a totally valid question! Thank you for raising it.)

Cheers,

JT

JT,

Your points are well made. Yes, my view is more specific. Most of my colleagues never make into theaters, including myself, with our films. But the ones who do, must split with the indie distributor.

Thanks for doing all this work. Its very interesting. I hope to apply it to my next project.

Tim

Many thanks Tim.

– I could not do all this work without many helpful people – such as yourself – making excellent points! – I think it is important to question, and to re-check everything… even when, we think it may be correct… And – You have also given me some ideas for further research! So – thank you again so much.

Ironically, it is possible “the future of cinema” is not in theatrical cinemas anyway… So – even making a feature (however it may then be distributed) I absolutely consider: a remarkable achievement. All the best with your projects.

Also – my new book with all this stuff in it (similar to the Blog but also with some new content) should come out in about a week on Amazon. (I will only charge $1 for it.) So – If you should happen to get time to look at it, I would certainly welcome any thoughts/feedback on it as well.

Many Thanks Again,

Best,

JT

Pingback: StoryAlity #121 – How to build a Box-Office Bomb: Base it on a Board Game! | StoryAlity

You left out tax in your calculation. That is almost another 40% of their money just completely gone.

I guess if you say you need 373% AFTER taxes, then the calculations would be solid.

# “percentage”

You mean “percent”.

No, they are not the same.

Pingback: HOW EXACTLY DO MOVIES MAKE MONEY? - SebConceptFilms

Pingback: Make ’em Laugh: The Return of (Good) R-Rated Comedies. – Fantasy Movie Draft